THE GREAT JOURNEY

"OF KLONDIKE KATE"

KATHERINE RYAN FROM JOHNVILLE, N.B.

CANADA

Far away from here, there is a river. A bright, tumbling torrent of water crashing over rocks and swirling down among the mountains.

Many years ago, in the winter months, it became a highway. Confined under a ten-foot layer of ice and snow, the river was a treacherous road where horses traversing its surface crust could suddenly vanish and drown not in its waters, but in its snow. Temperatures could veer wildly and the winter nights would become achingly cold or miserably soggy. Men shouldered enormous packs and piggy-backed them about three hundred feet before turning around and retrieving yet another pack for the short journey to its mate. Day after day they hopscotched up the river bed.

Into this world of enormous physical hardship stepped 28-year-old Kate Ryan on one winter's day in 1898. She was making for Glenora, all on her own. She was making for the Klondike.

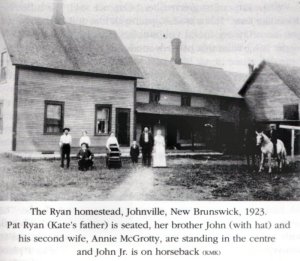

Katherine Ryan grew up in Johnville, a rural community located northeast of Bath in Carleton County, New Brunswick. The youngest of the Ryan children, she had a sound education and a happy childhood. She had a place in her community. She had prospects.

Kate Ryan had been courting Simon Gallagher. The Gallaghers were the local gentry and the Ryan's openly sported with Kate on her good fortune at snaring young Simon. Mama Gallagher watched with steely eyes. The Ryan's were poor, not from town. They were not notable, not distinguished, not worthy. No son of hers would ever marry a poor Ryan, she vowed, not while her hand was gripping the purse strings. Mama Gallagher would see to it and she did. She insisted her son enter the seminary.

Bereft, Kate needed to leave, needed to put some distance between herself and Johnville. An ill cousin's plea for help in Seattle provided just the chance. With her mother's love, Kate boarded the train in 1893 and never looked back.

Seattle was a bewildering swirl to Kate. Used to the narrow social horizons of rural New Brunswick, Kate stood amidst the growing bustle of an American port city. People from all corners of the world rushed by on the street. For the first time in her life, she saw men and women who were not white. Wagons careened down streets, pedestrians strode on their errand, saddle horses and carriages jostled for space while groups of prosperous-looking men stood talking and laughing on the street corners. Children darted in and through the crowds on business of their own while hawkers bawled in the marketplace. It was an assault on her senses - new sights, smells and the never-ending noise.

Traffic through the house was constant. Business associates, social contacts and entertaining consumed her until her cousin recovered from her illness. With less to do, Kate applied for a nursing position at the Nahomish hospital. She had a natural gift for the job and in two years, she was a confident, caring nurse. But Kate had itchy feet. The wandering ways of her father had found fertile ground and now her eyes turned northward to Vancouver.

Old friends from Johnville had flowed west and urged her to join them. The greatest attraction for Kate was the mountains. Towering over the landscape, they filled her mind as they filled the horizon. Often she would sit and meditate on the mountains, gradually giving over to an intense desire to see them, to walk them and to find out what lay behind them. What secrets did they hold for her? What could she discover from their communion? She already knew urban living held no mystique for her. The city was oppressive and suffocating. As she herself said, "I hunger to make my abode where the works of nature and not man abound."

She had the desire but lacked the opportunity. She needed a spark, something to push her on to her mountain destiny. In 1897, in the muck of a nondescript creek in the faraway North, three itinerant prospectors gave her the fuel she needed. Gold. The rush to the Klondike was on.

Gold fever exploded like a bomb on the continent and its echoes were felt well beyond. Men walked out the door, left everything behind, and struck out for the Klondike. Men who knew nothing of prospecting, who had never spent much time in the outdoors suddenly found themselves deep in the bush looking for the motherlode. Gold raged like an infection in the minds of North Americans. It was as common as a pulse.

Instantly it seemed the stores in Seattle and Vancouver carried everything anyone might need for a run to the Klondike. People weren't even sure where the Klondike was, was it Canadian or American? It didn't matter. There was gold in the hills and determination would see it came out.

Newspaper boys screamed the headlines and Kate, on her way to work on a sunny morning, was struck still as if by a sudden paralysis. Quashing her mounting excitement, she passed bubbling clutches of city residents and continued on her way. In the days and weeks ahead, Kate made up her mind and made her preparations for the final, ultimate act. That decision would make her a legend and gave the world "Klondike Kate."

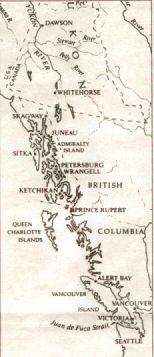

Leaving Vancouver on Feb. 28, 1898, she made her way by steamer to Wrangell, Alaska, previously a wood stop for the steam ships and now the muddy starting point for the Stikine River route.

Populated by other Klondike hopefuls, as well as those out to find their gold in the stampeders' pockets, Wrangell was notorious and Kate was warned to keep her wits about her. American ferry outfits were doing everything they could to inconvenience travellers and keep them stranded aboard for the gambling and liquor each boat provided.

Deliverance came from a young policeman who couldn't cook. Kate took pity on the bewildered George Chalmers who gratefully accepted her offer to take over his duties. In a gesture of thanks and respect Phillip Primrose, the officer in charge, included her as part of his company and Kate, with a police escort, hit the Stikine River Route.

It was a brutal trail. Horses had to be lightly loaded or they'd flounder in the snow. The group was in a constant race against the weather. Should it warm, the river would once again turn into a racing torrent and all hope of reaching Glenora, the next step in the quest for the Klondike, would be lost. Yet Kate persevered.

When the Northwest Mounted Police stopped and made a permanent camp, Kate continued on alone. While tens of thousands would eventually head to the Klondike over the years, most took the Chilicoot Trail from Skagway, Alaska. Kate was taking a less travelled route and her status as a single woman made her not just a rarity, but also something of a mystery to the men she met on the trail. If her solitude surprised them, her mission did not. They were all going to Glenora.

Buried deep in the interior, Glenora was a tiny settlement of just a few dozen people. Overnight it seemed, the population swelled to 3,000 as prospectors and dreamers rushed in to take advantage of the railroad which Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier's government promised would be built to carry them right into the Klondike's heart.

Kate stayed the summer in Glenora, operating her first restaurant as part of a newly-constructed hotel. When no rail service materialized, Kate and all the others realized they'd have to make the next stage of the journey themselves. The trail was long and laborious; from Glenora to Telegraph Creek on horseback following the Stikine River, on to the Teslin Trail after the river became too dangerous to follow.

Sturdily mounted astride her horse, Kate led a string of pack horses up the trail, through days of muskeg and mosquitoes, through forests burned black from the summer fires. Up at 3 a.m., she ate breakfast and then packer her animals carefully and, with luck, she was on the trail by five. Once in the saddle, she wouldn't stop until she reached her night's rest. Day after day it went on and yet Kate, despite all the deprivation and the never-ending work, remained cheerful.

When she first arrived in Teslin City, a collection of hovels and tents, she hoped her stay would be short and that she'd be able to make the Klondike by winter. But once again, government promises of transportation faded away like mist in the morning.

Making a trade with a man heading back down the trail, Kate swapped her horses for a sled and dog team. Although her plan of opening a restaurant wasn't possible due to a lack of supplies, she found her nursing skills were in high demand. Life was hard and injuries were common for the men who navigated the northern trails. Kate never turned the sick away and took money only from those who could afford it.

A friend she had made in Glenora, a Presbyterian minister name John Pringle, sent word from farther up the trail that her medical ability was needed at the Atlin camp, 60 miles away. Promising a young coureur de bois her dog team and sled if he guided her and her supplies, the pair headed out over the harsh mountain pass in late November. Temperatures plunged to -60 degrees, but in five days Kate found herself in Atlin for the winter of 1898.

It was an unforgiving and brutal season. Atlin consisted only of a few long buildings and half-a-dozen tents. Kate herself based her operations - besides nursing the sick, she took in washing and started another restaurant - in a 12 feet by 14 feet canvas tent with a dirt floor. The hardy souls stranded in Atlin for the winter clung to each other for the will to survive their surroundings. Kate organized a Christmas dinner to which everyone donated what they had. Kate herself donated her last six potatoes from supplies her father had sent to her.

When spring finally came, the warming sun summoned out a shambling wreck of humanity. Men suffering from scurvy, malnutrition, frost bite and exposure peered owlishly out from their doorways and took in the first rays of golden sunshine with grateful relief. The respite was brief. The rush resumed. With the mud and muck shifting with the melting snow, the river beds coyly offered more gold to the prospector's pan and pursuit of the hidden wealth intensified.

Determined to press on to the Klondike itself, Kate packed up her meagre, tattered belongings and walked the trail. Across Atlin Lake to Taku, up Taku Arm to Nares Lake and over to Caribou Crossing. She was ecstatic. Her long-held dream of the Klondike came nearer with every stride she made through the wild country.

Finally, Kate stood on a rise and looked at Whitehorse, still a town of tents, but in her eyes, the Promise Land. She had arrived. She was in the Klondike.

A living was what was needed now that she had achieved her goal. Up went the tent, a pot of coffee on to boil and a sign outside the door: Kate's Café - Open For Business. Word spread of Kate's arrival in Whitehorse and old friends from Glenora and Telegraph Creek and other stops up and down the trail stopped by and congratulated her on her achievement. She was already a popular and well-known personality. Although every day brought newcomers into town, Kate's generosity, kindness and the sheer novelty of a woman alone in the Yukon had made her famous. The nickname Klondike Kate was bestowed on her like a title and her various exploits became legendary.

As Whitehorse grew, Kate's establishment kept pace until at last, she decided that living in a tent for two years was long enough. A house was wanted and she meant to have one. It was one of the first frame houses in Whitehorse.

Her café quickly outgrew her little one room cabin and when a local hotelier offered her space in his new establishment, she took him up on it. She began a building fund for a Catholic church to be built in Whitehorse, she grubstaked miners and then kept an able eye on her investments. She patched up the injured, took in washing. Her stature, and the legends around her, grew.

Finally, the Northwest Mounted Police approached Kate with a special request. Across the tracks in Whitehorse there was a rather singular district. Aptly named Lousetown, it was populated by women and their business associates who also had a stake in the miners. Dance hall girls, girls with rooms in back where they would retire upon request, sought to lighten the miners' pockets.

In 1900, the police force was under pressure to tidy things up in Lousetown but the trouble of dealing with these rough, but nevertheless, female prisoners confounded the proper Victorian gentlemen in uniform. Some time after Parliament passed a law in February 1900 allowing a "woman special" to be hired to assist any member of the Northwest Mounted Police with a woman prisoner, Kate Ryan was the first woman hired as a "constable special" attached to the Northwest Mounted Police, Whitehorse. She was hired to be a guard for women in the Whitehorse jail. This she did, like everything else, capable and confidently.

She was a strong, imposing woman at almost six feet tall. None of her charges ever troubled her in the jail, but one, a young woman given one month hard labour in 1902, would return to haunt Kate endlessly down the corridor of her life.

Kitty Rockwell was a singer, a dancer and a thief. She was a woman of colourful reputation and when she arrived in Whitehorse, the town was stood on its ear. It had been two years since the sort of shenanigans Kitty specialized in had been practised much in Lousetown and the police force moved in quickly to shut her down. She was a prostitute but, even so, the sentence of 30 days hard labour was a stiff one for the time. Very few women were ever given a comparable detention and young Kitty's penchant for well-and-truly scalping her clientele earned her a remarkable sentence in the Whitehorse jail.

Deported at the end of her term, she managed a quick return to the Klondike as a dancer in the Dawson theatres with a Victoria-based troupe. She was a star in her world and she fell in love with a shifty saloon waiter named Alexander Pantages.

Together, the pair built up the Orpheum Theatre in Dawson and then left to manage nickelodeons in Seattle and Victoria. Pantages was willing to make use of Kitty's charms to further his own business goals. In 1903 Kitty went back up to Dawson to sweet-talk some money out of an old mining acquaintance. Pantages used the money Kitty sent him to finance the purchase of a theatre in Seattle, and, while his lover was too far away to do anything about it, he married an 18-year-old violinist.

Kitty was furious. Stoked with rage, she filed suit in 1905, alleging breach of promise. Kitty was a professional performer. She made grand entrances before hoards of reporters. She fashioned for herself a legend and she took the name "Klondike Kate."

Back home, across the country in Johnville, Kate Ryan's friends and acquaintances were puzzled and growing more and more dismayed as the lurid details of Kitty Rockwell's life, under her moniker of Klondike Kate, bled onto the reputation of their own native daughter. Kate Ryan had been home in 1901 and had been amazed by the stories about her that she encountered moving across America and then home in New Brunswick. People gawked at her in church, socials were planned in her honour. The name Klondike Kate had travelled across a continent bearing tales of her fortitude, kindness and immense accomplishments.

She was beloved by her wide circle of friends in the North and proudly proclaimed by her home town. And now this, these sordid stories spilling from the papers of the day told quite a different story about Klondike Kate. Kitty Rockwell well laid claim to some of the more famous acts of courage credited to Kate Ryan and she knew exactly what she was doing. Kitty knew Kate and doubtless from her time in the Whitehorse jail, was quite happy to make dog meat of Kate's reputation.

In conservative Catholic Johnville, prostitution and adultery were the most scarlet of sins and Kate, once she had been informed of the source of the rumours, did her best to assure her family of the truth. For the world at large, it was already to late. Kate Ryan, one of the brightest lights in the Yukon, saw her star dragged from the heights and slung into the mud at the feet of a vengeful and avaricious prostitute.

What had once been a name of affection became a canker on her heart. Knowing that people looked at her and wondered if all the stories were true, Kate held her head up, squared up her shoulders and carried on. She now had the sons of her widowed brother to raise and a business to run. Not only that, there was the work she had begun in 1903 as a female gold inspector, searching for any gold being smuggled out of the country, with the North West Mounted Police. She maintained her community activities and those who knew her, knew the truth.

Life continued in Whitehorse. Her nephews provided focus and her endless work occupied her body while friends distracted her mind. An occasional bit of intrigue would provide some excitement, as when she agreed to allow a smitten young police constable to meet his sweetheart in her living room, or when one of the more notorious Lousetown madams needed a secluded room in which to die of measles. She recovered. Kate patched and mended bodies and provided gentle care for weary minds.

Over many years, Kate lived and loved the Klondike. As she grew older, life seemed to grow harder in the ways that matter most. Accustomed to physical work, she was dragged down not by her vocation, but by her losses.

Her cherished godson, one of her resident nephews, was lost tragically in the sinking of the steamship the Princess Sophia. Burdened by heartache, Whitehorse no longer offered refuge and other horizons called her. Once again, she pulled up stakes in 1919 and moved on, this time to Stewart, British Columbia.

Surrounded again by the mountains, those serene of her younger years, Kate felt she'd come home. She settled into a new job as a Commission Agent and became a part of the vibrant social whirl. Late in 1923, Kate returned for a last visit to Johnville. Misunderstandings over the Kitty Rockwell saga were overlooked, if not exactly explained, and Kate was once again a celebrated hero. Little children were at a loss for words, all big eyed and wondering, when they caught a glimpse of her. Returning home, she lived contentedly with the familiar, secure and reassuring mass of mountains around her.

Kate's life ended peacefully in Vancouver in 1932. She chose a difficult path, like the trails she travelled, and she had done the best she could. She was laid to rest where she could still see her mountains.

She never married, never had children, but in her spirit she has many descendants. She ventured where many aspired but few achieved. She endured, persevered and thrilled the heart of those fortunate enough to have seen her. The creek behind her house in Stewart was name Kate Ryan's Brook by the local children and even today, her legacy is such that her homes are marked, if not by monuments, then by memories.

Most recent revision November 14, 2015

Alton Morrell-Contributed by Ann Brennan, the undisputed expert on the life of Kate Ryan, or Klondike Kate, lives in Johnville, within sight of the Ryan homestead. Over years of research, Mrs. Brennan has assembled a formidable mountain of material chronicling, piece by piece, the true story of Klondike Kate; The New Brunswick Telegraph and a special thanks to Julie Byram for her special contribution.